This is about a storm some call Helene and others call Capitalism, Greed, Callous Neglect or the slow and then rapid degradation of the one and only Earth we’ve got. But it is also about a people, and all the ways they (and we) do our best to work miracles of collective care amid a backdrop of loss, devastation, and the history of dehumanization and extraction that animated the Industrial Revolution, and continues to this day.

This a story about hope, resilience, and transcendental kinship more than it is about loss; this is a story about the inextricable rhizomatic linkages we have with one another, about how we survive it all, be it the disaster of climate catastrophe, or the disaster of rent.

This is a story about home, and getting back there.

Asheville, North Carolina had once been called a climate haven. Because of its location in a temperate zone, far from the impact of tornadoes, hurricanes, and sea level rise, people looking to put down roots in this mountain city believed they would be safe from the destructive forces witnessed to the South, and East Coast.

Just one day after making a crushing landfall as a category 4 hurricane in Florida, where storm surges, some up to 15 feet, were described as “unsurvivable”, Helene arrived, and everything changed for Southern Appalachia, and especially the highlands of Western North Carolina. No place is safe from the cascading consequences of climate degradation.

The storm carved a 500 mile path of destruction, impacting no less than 6 states in total. By the time it reached Western North Carolina, it was said to be a tropical storm, but this did little to quell its fury. Photos coming out of Buncombe and Henderson counties, as well as some Eastern Tennessee counties, the day before were already showing water up to car windows, an already worryingly swollen watershed.

In most places, no evacuation orders were given until the water had already begun to rise. Surely, everyone thought, not here.

What happened next, no one had foreseen. As the watershed flooded and spilled out all over the region, people escaped to higher ground, climbing to the roofs of their homes to escape the flood that was later described as “a blender that was just taking out anything in its path”. Hundreds of mudslides occurred, some of them filled with toxic run-off from damaged plastic and chemical plants, creating hazmat zones where towns once stood, swaths of old forest cast aside like toothpicks, roadways and highways just washed away.

In a little under 48 hours, thousands of square miles of the southeast US became unrecognizable.

When the water receded, and we saw the full extent of the damage, many were left to conclude that so many small towns, and even large sections of cities the size of Asheville, were simply “gone”.

But, in reality, they are not “gone”. Cities and towns are more than the sum of their buildings, their roads, their communications infrastructure. They are people. They are the community that brings a place to life. And none of that is gone in Southern Appalachia. None of that is gone in Western North Carolina.

Even while the flood was still raging, people rescued neighbors, family members, and friends. When the lights are out, and all we have is each other, we have learned again and again, that humans rise to the occasion, and we do so together. In these moments when all of the things that keep us apart fade away, in the aftermath of these traumatic moments, we find our salvation in the unbreakable bonds between us.

Almost immediately, spontaneous mutual aid began occurring in the hills and hollers, in the projects and on the reservations, with folks rushing to share resources, to bring food and water, to offer what shelter they had, even if all they had was a tent.

Almost immediately, people from all over the country began responding by mobilizing convoys of box trucks, chainsaws, and medical workers.

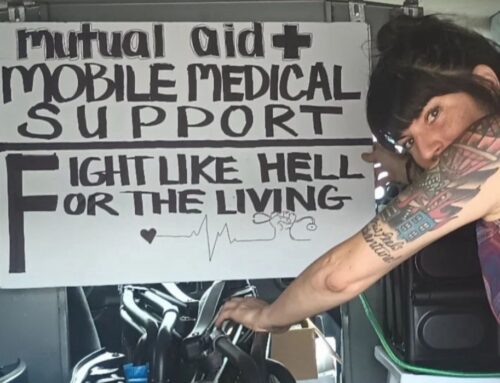

As always, Mutual Aid Disaster Relief locates itself in this most organic, most natural symphony of care. Working in collaboration with our co-conspirators on the ground, we are directed by the needs of those impacted the most, those forgotten, those underestimated, the marginalized and relegated who know bone deep that “come hell and highwater” we keep us safe.

Our thoughts return to Lumberton, North Carolina. After Hurricane Florence caused several dams to fail, and the Lumber River ran out over Robeson County, a ragtag bunch of merry folks with radical love in our hearts established a temporary home in a donated warehouse. While the rusty water still stood, we found our way and allowed ourselves to be changed by what we saw and what we learned. We believed, more than ever, in the power of people remembering their power, and resolving to share it. We became committed to spending the rest of our lives trying to inspire people to hope in the face of surge and wind, to unify with each other, to rise to every challenge that faces us, and we do this because people who’d lost everything but their hearts and dignity showed us how.

It is fitting then, that years and storms later, we find ourselves again in rural North Carolina, a place so frequently overlooked, a place so frequently stereotyped, but where we have witnessed more beauty in mutual aid, as a way of life, than we could ever convey with words.

To reference a country song that you’d be hard pressed to ignore at any gathering in the region — these are the best “friends in low places” a person could ask for. The ones who were there all along, living side by side with us, even if we had all been too alienated by the speed of this society to find each other. Here, we find each other, in a smiling face, a warm embrace, a good belly laugh in a dark time, a shared meal, or cleansing tears cried together.

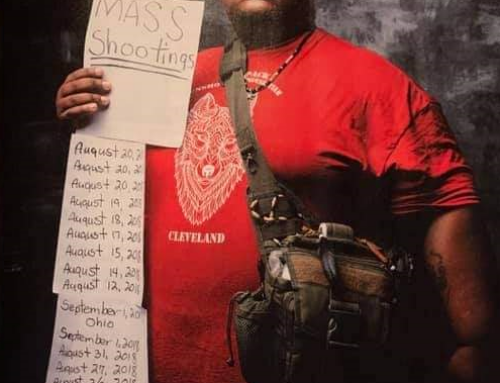

Days after Helene struck Western North Carolina, FEMA announced that its budget was 9 billion dollars short. Just one day before that, the US government sent $8.67 billion in aid to the apartheid state of Israel’s genocidal efforts in Gaza and the West Bank. These numbers are stark, the connections between struggles laid absolutely bare. This reminds us that from Rafah to the Weelaunee forest, from Jenin to Unicoi County, Tennessee, and wherever state forces attempt to criminalize the act of loving one’s neighbor, people’s love is more powerful and there is no struggle for liberation, for humanity, that is not connected.

To that end, Mutual Aid Disaster Relief, friends, allies, and co-conspirators have mobilized to respond to the destruction of Western North Carolina. With hubs popping up in Asheville, Burnsville, Barnardsville and beyond, we are pushing out critically needed resources to communities that are still trapped behind broken roads and mudslides. We are assembling work crews to muck and gut flooded homes. We are coordinating medical responders to do wellness checks, to offer first aid, and to give assistance navigating getting needed medications or higher care.

We have shared generators, well test kits, water filtration systems, tools and PPE for work crews, communications infrastructure support, buddy heaters, as many hugs as any person could ask for, and we have shared in mourning and deep sorrow.

Many of us find ourselves in the position of not only being impacted by this storm, our own jobs and homes damaged, but also of pouring ourselves into the long work of recovery in our communities. It is impossible to watch us, to join us, without coming to understand that the people we are when we are caring for one another, when we are holding one another, are the very people we always hoped we were. We are the answer we’ve been looking for.

Helene has done nothing if not lay us bare, bringing to the surface all of our red mud-stained childhood memories. Those water towers we climbed with our cousins, those fishing holes our parents and grandparents taught us to swim in, those places we know very well were experiencing the disaster of resource extraction, labor extraction, and artificially enforced scarcity long before Helene found its way to the rivers surrounding Asheville.

The history of Appalachia, many say, is a history of human sacrifice to capital, to the mines and the looms, to the company towns and the coal camps. The history of Appalachia is one of gawking outsiders come to marvel at the supposedly “backward” inhabitants. But the history of Appalachia is so much more than that.

Just as the Peoples’ history of the South more broadly is the history of resistance against the forces of white supremacy and other forms of vampiric extraction, the Peoples’ history of Southern and Central Appalachia is a history of resilience and resistance against these forces, from the Coal Wars of the early 20th century to ongoing struggles surrounding pipelines, fracking, and clean water.

The history of Appalachia is a history of people taking care of one another, a culture based on honor, integrity, care, and the awe inspiring resilience of the human spirit. A place typically represented as monolithically white, Appalachia is home to vibrant Indigenous communities, Afrolachian and Mexilachian communities, Appalachia has welcomed refugees from all over the world, most recently including Ukrainians fleeing with their families from another imperial war machine. It is home to the so-called “tri-racial isolate” Melungeon community, who pride themselves on the fact that they have “kin of all colors”, and whose very existence flies in the face of every lie we have been told about colonial constructs like blood quantum and racial castes. It is an ethnically, politically, religiously, culturally diverse region that is nothing if not a testament to tapestry.

For many families and individuals now without shelter, winter is coming soon, and the future is uncertain. In some places it could be months before power is restored, while some remain trapped in towns and homes, without roads in or out, as of this writing.

As the news cycle has given coverage surrounding Helene the full election year treatment, with distant politicians from every ideological corridor of the empire rushing to blame the other team and garner praise for themselves, we know, and the people impacted by this storm know, that regardless of what happens in November, we are each others’ only hope.

The news cycle moves at the speed of light, but the task of rebuilding after a disaster of this magnitude is a work that goes on for many years, in the immediate aftermath and recovery, and in the work of intervention upon, and resistance to, disaster capitalism.

Appalachia will still be here when the dead are known and mourned, when the rebuilding is complete; Appalachia will still be here, because its people will still be here.

Mutual Aid Disaster Relief will be here too. Both this network, and the wider work of mutual aid [as] disaster relief that cannot be contained by any single network, person, or organization. We will never give up on each other, or the mountains and hills we all belong to.